Amanda's NICU ED Blogs

RECENT BLOG ARTICLES

Abdominal Wall Defects

Abdominal Wall Defects

Today, I want to highlight a few abdominal wall defects. Have you ever cared for a baby with an abdominal wall defect? Let's discuss two different types of abdominal wall defects: Gastroschisis and Omphalocele.

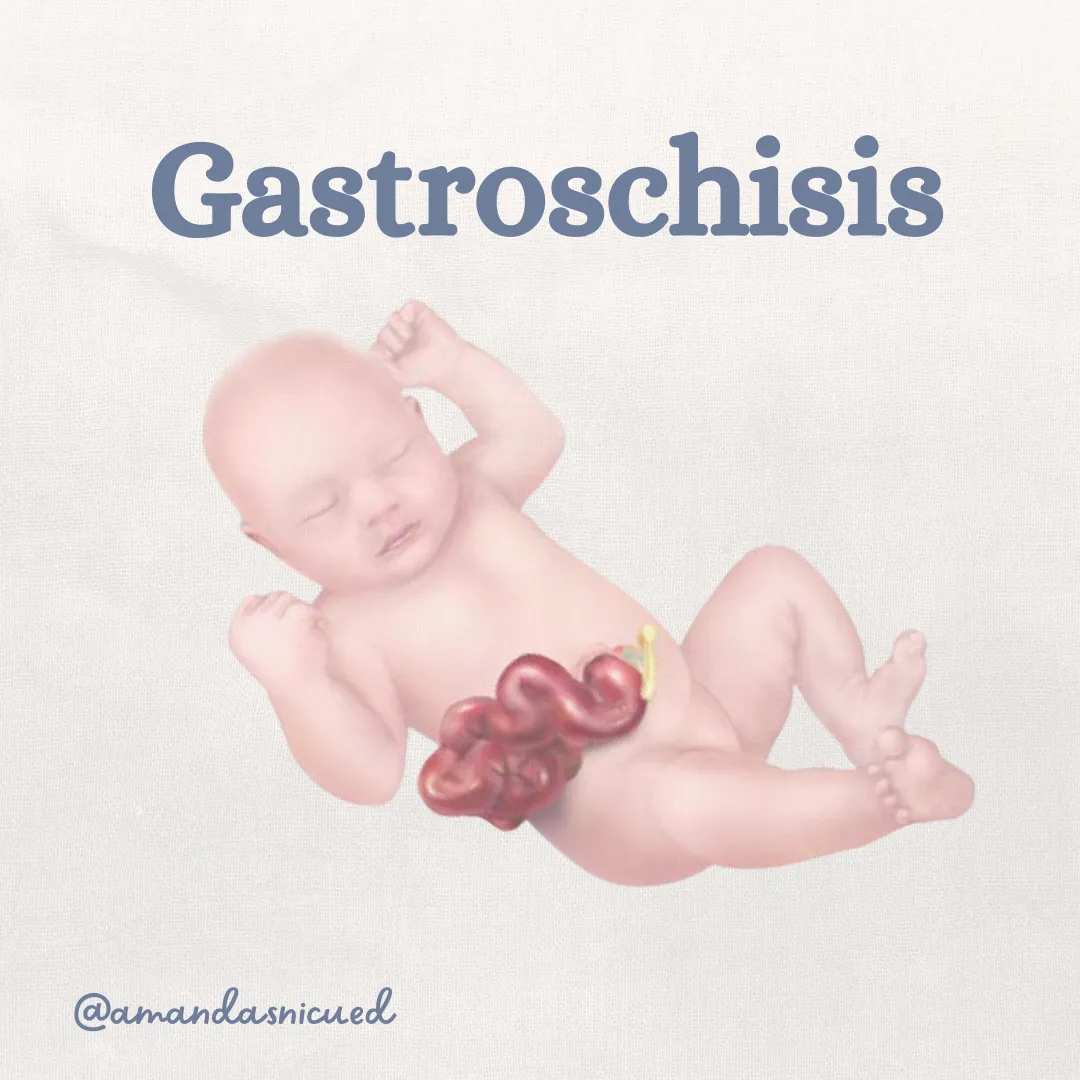

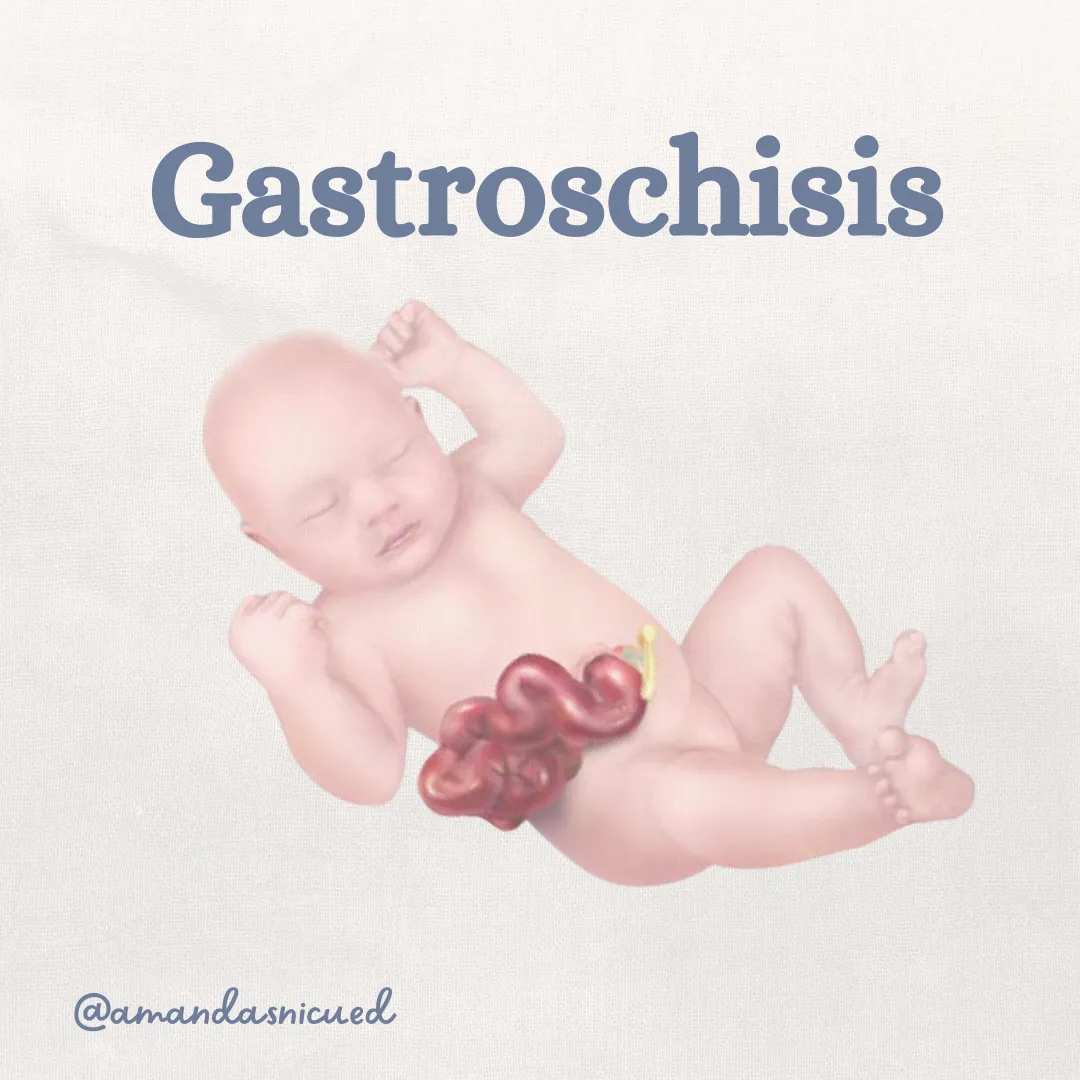

Gastroschisis:

In gastroschisis, the newborn is born with abdominal organs protruding through a defect located to the right of the umbilicus. This can be detected prenatally through elevated alpha-fetoprotein levels and confirmed via ultrasound. While the exact cause is unknown, gastroschisis is believed to result from occlusion of the omphalomesenteric artery, leading to abnormal abdominal wall development.

At birth, the exposed organs often appear thickened, inflamed, and edematous due to exposure to amniotic fluid. During neonatal resuscitation, the lower body and abdomen are placed in a clear, sterile bag. This serves to protect the exposed viscera, prevent heat and fluid loss, and support thermoregulation. The infant’s temperature must be closely monitored because of their high risk for heat loss.

Other considerations for babies born with gastroschisis include keeping the umbilical cord long (10–20 cm), as it may be used in surgical repair. Positioning the baby on their right side helps prevent kinking of the vessels supplying the viscera. Monitoring the exposed viscera for signs of poor perfusion is critical. A large orogastric or double-lumen sump tube should be placed to prevent gaseous distention of the bowel.

Dingeldein, 2025

Fluid management is another key aspect of care for these babies, as they have increased fluid requirements due to the large losses associated with the defect. IV access is crucial, but avoid placing IVs in the lower extremities due to the weight of the herniated viscera and the risk of increased venous pressure.

Collaboration with the pediatric surgery team is vital, as they will manage the closure of the defect and address any associated intestinal atresias (which occur in 5–25% of infants with gastroschisis). Surgical repair may be done through primary closure, where the viscera are returned to the abdomen all at once. Some institutions now use a "sutureless technique," where the bowel is returned to the abdomen and the umbilicus is placed over the defect with a dressing. The defect then closes without the need for sutures—pretty cool, right? Check out this photo of a sutureless repair before the dressing is applied.

Chabra, Anderson & Javid, 2024

If the defect is too large for primary repair, a staged repair may be used. In this approach, the exposed viscera are placed in a silo and slowly returned to the abdominal cavity over a week. Nursing care during this time involves closely monitoring respiratory status and perfusion of the bowel and body below the defect. The returning organs can increase abdominal pressure, which may impair ventilation by pushing up on the diaphragm or cause compartment syndrome by restricting blood flow. Nurses also play a key role in preventing infection and managing the infant’s pain.

Infants with gastroschisis may experience delayed return of bowel function due to damage from amniotic fluid exposure, which can delay the progression of full enteral feeds and prolong hospitalization. Nurses are essential in supporting families through this extended hospital stay. Overall, babies born with gastroschisis have good outcomes with a >95% survival rate.

Omphalocele:

Omphalocele is another abdominal wall defect, though it is less common than gastroschisis. In omphalocele, the viscera protrude through a defect at the base of the umbilical cord but remain covered by a protective amniotic membrane. The etiology of omphalocele is multifactorial, with both environmental and chromosomal factors contributing. The embryologic abnormality involves abnormal folding of the germ disc, which occurs around week 5 of gestation. This failure to fold into a tubular structure results in a defect of variable size at the umbilical ring.

Omphalocele is often associated with other anomalies, including cardiac defects, intestinal malrotation, neurological abnormalities, genitourinary malformations, skeletal anomalies, and chromosomal defects (e.g., trisomy 13, 18, 21, and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome).

Like gastroschisis, omphalocele can be detected via elevated alpha-fetoprotein levels and diagnosed by ultrasound. Amniocentesis is offered to assess for chromosomal abnormalities.

During neonatal resuscitation, the defect is protected with a sterile plastic bag, and NRP recommends the infant is positioned on their right side to preserve blood flow to the viscera. It is important that the defect is handled very gently to prevent rupture of the membrane. Infants with a large omphalocele may require respiratory support, such as CPAP or mechanical ventilation due to pulmonary hypoplasia and/or pulmonary hypertension.

The size of the defect determines the treatment plan. Surgical options are similar to those for gastroschisis, but the protective membrane means that complete closure may be less urgent. For smaller defects, surgery may be completed early, but for giant omphaloceles, full closure may take months.

Wagner & Cusik, 2019

For giant omphaloceles, a "paint and wait" approach may be used. This involves the daily application of an antimicrobial agent (such as silver sulfadiazine) and a dressing to encourage epithelialization of the membrane, allowing the infant to grow before definitive surgical closure is attempted. The growth of the abdominal cavity allows the herniated viscera to reduce back into the abdomen with gravity alone or with mild external compression. Lung growth over time will also improve the baby’s ability to tolerate an operation and an abdominal closure. The eventual repair of the abdominal wall can be done several months or even years later.

In cases that the membrane is ruptured and the defect is very large, a staged surgical repair can be performed. This involves placing a silo for serial reduction, followed by definitive closure.

The outcomes of babies born with an omphalocele depends on the associated anomalies. There are risks of long term morbidities such as feeding intolerance, failure to thrive, GE reflux, hernias, chronic lung disease, neurodevelopmental and motor delays. Those with giant omphaloceles have increased risk of morbidity and mortality due to the large defect coupled with pulmonary hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension.

NICU nurses play a crucial role in supporting families with babies who have abdominal wall defects by providing comprehensive care and emotional reassurance. We educate parents about the condition, explain treatment plans and the expected course of care, which helps alleviate anxiety. By fostering open communication, nurses encourage families to ask questions and express their concerns, creating a supportive environment. Additionally, we offer practical support, such as guidance on feeding and bonding with their infant. This holistic approach not only enhances the care of the infant but also empowers families during a challenging time. Have you taken care of these babies and their families? I'd love to hear about your experience.

Amanda xoxo

Missed my other newsletters? Click here to read them!

Let's Study Together! Join my Certification Course

References:

Dingeldein, M. (2025). Selected gastrointestinal anomalies in the neonate. Fanaroff and Martin’s Neonatal Perinatal Medicine (12th Ed). Elsevier.

Gallagher, M., Pacetti, A., Lavvorn, H., & Carter, B. (2021). Neonatal Surgery. Merenstein & Gardner’s Handbook of Neonatal Intensive Care (9th Ed). Elsevier.

Wagner JP, Cusick RA. Paint and wait management of giant omphaloceles. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28(2):95-100. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2019.04.005.

Chabra, Anderson & Javid, (2024). Abdominal Wall Defects. Avery's Diseases of the Newborn (11th Ed.) Elsevier

OBimages. (n.d.) Gastroschisis Omphalocele. Retrieved from https://obimages.net/free-gastroschisis-omphlocele/

Respiratory and Blood Gas Blogs

Abdominal Wall Defects

Abdominal Wall Defects

Today, I want to highlight a few abdominal wall defects. Have you ever cared for a baby with an abdominal wall defect? Let's discuss two different types of abdominal wall defects: Gastroschisis and Omphalocele.

Gastroschisis:

In gastroschisis, the newborn is born with abdominal organs protruding through a defect located to the right of the umbilicus. This can be detected prenatally through elevated alpha-fetoprotein levels and confirmed via ultrasound. While the exact cause is unknown, gastroschisis is believed to result from occlusion of the omphalomesenteric artery, leading to abnormal abdominal wall development.

At birth, the exposed organs often appear thickened, inflamed, and edematous due to exposure to amniotic fluid. During neonatal resuscitation, the lower body and abdomen are placed in a clear, sterile bag. This serves to protect the exposed viscera, prevent heat and fluid loss, and support thermoregulation. The infant’s temperature must be closely monitored because of their high risk for heat loss.

Other considerations for babies born with gastroschisis include keeping the umbilical cord long (10–20 cm), as it may be used in surgical repair. Positioning the baby on their right side helps prevent kinking of the vessels supplying the viscera. Monitoring the exposed viscera for signs of poor perfusion is critical. A large orogastric or double-lumen sump tube should be placed to prevent gaseous distention of the bowel.

Dingeldein, 2025

Fluid management is another key aspect of care for these babies, as they have increased fluid requirements due to the large losses associated with the defect. IV access is crucial, but avoid placing IVs in the lower extremities due to the weight of the herniated viscera and the risk of increased venous pressure.

Collaboration with the pediatric surgery team is vital, as they will manage the closure of the defect and address any associated intestinal atresias (which occur in 5–25% of infants with gastroschisis). Surgical repair may be done through primary closure, where the viscera are returned to the abdomen all at once. Some institutions now use a "sutureless technique," where the bowel is returned to the abdomen and the umbilicus is placed over the defect with a dressing. The defect then closes without the need for sutures—pretty cool, right? Check out this photo of a sutureless repair before the dressing is applied.

Chabra, Anderson & Javid, 2024

If the defect is too large for primary repair, a staged repair may be used. In this approach, the exposed viscera are placed in a silo and slowly returned to the abdominal cavity over a week. Nursing care during this time involves closely monitoring respiratory status and perfusion of the bowel and body below the defect. The returning organs can increase abdominal pressure, which may impair ventilation by pushing up on the diaphragm or cause compartment syndrome by restricting blood flow. Nurses also play a key role in preventing infection and managing the infant’s pain.

Infants with gastroschisis may experience delayed return of bowel function due to damage from amniotic fluid exposure, which can delay the progression of full enteral feeds and prolong hospitalization. Nurses are essential in supporting families through this extended hospital stay. Overall, babies born with gastroschisis have good outcomes with a >95% survival rate.

Omphalocele:

Omphalocele is another abdominal wall defect, though it is less common than gastroschisis. In omphalocele, the viscera protrude through a defect at the base of the umbilical cord but remain covered by a protective amniotic membrane. The etiology of omphalocele is multifactorial, with both environmental and chromosomal factors contributing. The embryologic abnormality involves abnormal folding of the germ disc, which occurs around week 5 of gestation. This failure to fold into a tubular structure results in a defect of variable size at the umbilical ring.

Omphalocele is often associated with other anomalies, including cardiac defects, intestinal malrotation, neurological abnormalities, genitourinary malformations, skeletal anomalies, and chromosomal defects (e.g., trisomy 13, 18, 21, and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome).

Like gastroschisis, omphalocele can be detected via elevated alpha-fetoprotein levels and diagnosed by ultrasound. Amniocentesis is offered to assess for chromosomal abnormalities.

During neonatal resuscitation, the defect is protected with a sterile plastic bag, and NRP recommends the infant is positioned on their right side to preserve blood flow to the viscera. It is important that the defect is handled very gently to prevent rupture of the membrane. Infants with a large omphalocele may require respiratory support, such as CPAP or mechanical ventilation due to pulmonary hypoplasia and/or pulmonary hypertension.

The size of the defect determines the treatment plan. Surgical options are similar to those for gastroschisis, but the protective membrane means that complete closure may be less urgent. For smaller defects, surgery may be completed early, but for giant omphaloceles, full closure may take months.

Wagner & Cusik, 2019

For giant omphaloceles, a "paint and wait" approach may be used. This involves the daily application of an antimicrobial agent (such as silver sulfadiazine) and a dressing to encourage epithelialization of the membrane, allowing the infant to grow before definitive surgical closure is attempted. The growth of the abdominal cavity allows the herniated viscera to reduce back into the abdomen with gravity alone or with mild external compression. Lung growth over time will also improve the baby’s ability to tolerate an operation and an abdominal closure. The eventual repair of the abdominal wall can be done several months or even years later.

In cases that the membrane is ruptured and the defect is very large, a staged surgical repair can be performed. This involves placing a silo for serial reduction, followed by definitive closure.

The outcomes of babies born with an omphalocele depends on the associated anomalies. There are risks of long term morbidities such as feeding intolerance, failure to thrive, GE reflux, hernias, chronic lung disease, neurodevelopmental and motor delays. Those with giant omphaloceles have increased risk of morbidity and mortality due to the large defect coupled with pulmonary hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension.

NICU nurses play a crucial role in supporting families with babies who have abdominal wall defects by providing comprehensive care and emotional reassurance. We educate parents about the condition, explain treatment plans and the expected course of care, which helps alleviate anxiety. By fostering open communication, nurses encourage families to ask questions and express their concerns, creating a supportive environment. Additionally, we offer practical support, such as guidance on feeding and bonding with their infant. This holistic approach not only enhances the care of the infant but also empowers families during a challenging time. Have you taken care of these babies and their families? I'd love to hear about your experience.

Amanda xoxo

Missed my other newsletters? Click here to read them!

Let's Study Together! Join my Certification Course

References:

Dingeldein, M. (2025). Selected gastrointestinal anomalies in the neonate. Fanaroff and Martin’s Neonatal Perinatal Medicine (12th Ed). Elsevier.

Gallagher, M., Pacetti, A., Lavvorn, H., & Carter, B. (2021). Neonatal Surgery. Merenstein & Gardner’s Handbook of Neonatal Intensive Care (9th Ed). Elsevier.

Wagner JP, Cusick RA. Paint and wait management of giant omphaloceles. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28(2):95-100. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2019.04.005.

Chabra, Anderson & Javid, (2024). Abdominal Wall Defects. Avery's Diseases of the Newborn (11th Ed.) Elsevier

OBimages. (n.d.) Gastroschisis Omphalocele. Retrieved from https://obimages.net/free-gastroschisis-omphlocele/

Cardiac Blogs

Abdominal Wall Defects

Abdominal Wall Defects

Today, I want to highlight a few abdominal wall defects. Have you ever cared for a baby with an abdominal wall defect? Let's discuss two different types of abdominal wall defects: Gastroschisis and Omphalocele.

Gastroschisis:

In gastroschisis, the newborn is born with abdominal organs protruding through a defect located to the right of the umbilicus. This can be detected prenatally through elevated alpha-fetoprotein levels and confirmed via ultrasound. While the exact cause is unknown, gastroschisis is believed to result from occlusion of the omphalomesenteric artery, leading to abnormal abdominal wall development.

At birth, the exposed organs often appear thickened, inflamed, and edematous due to exposure to amniotic fluid. During neonatal resuscitation, the lower body and abdomen are placed in a clear, sterile bag. This serves to protect the exposed viscera, prevent heat and fluid loss, and support thermoregulation. The infant’s temperature must be closely monitored because of their high risk for heat loss.

Other considerations for babies born with gastroschisis include keeping the umbilical cord long (10–20 cm), as it may be used in surgical repair. Positioning the baby on their right side helps prevent kinking of the vessels supplying the viscera. Monitoring the exposed viscera for signs of poor perfusion is critical. A large orogastric or double-lumen sump tube should be placed to prevent gaseous distention of the bowel.

Dingeldein, 2025

Fluid management is another key aspect of care for these babies, as they have increased fluid requirements due to the large losses associated with the defect. IV access is crucial, but avoid placing IVs in the lower extremities due to the weight of the herniated viscera and the risk of increased venous pressure.

Collaboration with the pediatric surgery team is vital, as they will manage the closure of the defect and address any associated intestinal atresias (which occur in 5–25% of infants with gastroschisis). Surgical repair may be done through primary closure, where the viscera are returned to the abdomen all at once. Some institutions now use a "sutureless technique," where the bowel is returned to the abdomen and the umbilicus is placed over the defect with a dressing. The defect then closes without the need for sutures—pretty cool, right? Check out this photo of a sutureless repair before the dressing is applied.

Chabra, Anderson & Javid, 2024

If the defect is too large for primary repair, a staged repair may be used. In this approach, the exposed viscera are placed in a silo and slowly returned to the abdominal cavity over a week. Nursing care during this time involves closely monitoring respiratory status and perfusion of the bowel and body below the defect. The returning organs can increase abdominal pressure, which may impair ventilation by pushing up on the diaphragm or cause compartment syndrome by restricting blood flow. Nurses also play a key role in preventing infection and managing the infant’s pain.

Infants with gastroschisis may experience delayed return of bowel function due to damage from amniotic fluid exposure, which can delay the progression of full enteral feeds and prolong hospitalization. Nurses are essential in supporting families through this extended hospital stay. Overall, babies born with gastroschisis have good outcomes with a >95% survival rate.

Omphalocele:

Omphalocele is another abdominal wall defect, though it is less common than gastroschisis. In omphalocele, the viscera protrude through a defect at the base of the umbilical cord but remain covered by a protective amniotic membrane. The etiology of omphalocele is multifactorial, with both environmental and chromosomal factors contributing. The embryologic abnormality involves abnormal folding of the germ disc, which occurs around week 5 of gestation. This failure to fold into a tubular structure results in a defect of variable size at the umbilical ring.

Omphalocele is often associated with other anomalies, including cardiac defects, intestinal malrotation, neurological abnormalities, genitourinary malformations, skeletal anomalies, and chromosomal defects (e.g., trisomy 13, 18, 21, and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome).

Like gastroschisis, omphalocele can be detected via elevated alpha-fetoprotein levels and diagnosed by ultrasound. Amniocentesis is offered to assess for chromosomal abnormalities.

During neonatal resuscitation, the defect is protected with a sterile plastic bag, and NRP recommends the infant is positioned on their right side to preserve blood flow to the viscera. It is important that the defect is handled very gently to prevent rupture of the membrane. Infants with a large omphalocele may require respiratory support, such as CPAP or mechanical ventilation due to pulmonary hypoplasia and/or pulmonary hypertension.

The size of the defect determines the treatment plan. Surgical options are similar to those for gastroschisis, but the protective membrane means that complete closure may be less urgent. For smaller defects, surgery may be completed early, but for giant omphaloceles, full closure may take months.

Wagner & Cusik, 2019

For giant omphaloceles, a "paint and wait" approach may be used. This involves the daily application of an antimicrobial agent (such as silver sulfadiazine) and a dressing to encourage epithelialization of the membrane, allowing the infant to grow before definitive surgical closure is attempted. The growth of the abdominal cavity allows the herniated viscera to reduce back into the abdomen with gravity alone or with mild external compression. Lung growth over time will also improve the baby’s ability to tolerate an operation and an abdominal closure. The eventual repair of the abdominal wall can be done several months or even years later.

In cases that the membrane is ruptured and the defect is very large, a staged surgical repair can be performed. This involves placing a silo for serial reduction, followed by definitive closure.

The outcomes of babies born with an omphalocele depends on the associated anomalies. There are risks of long term morbidities such as feeding intolerance, failure to thrive, GE reflux, hernias, chronic lung disease, neurodevelopmental and motor delays. Those with giant omphaloceles have increased risk of morbidity and mortality due to the large defect coupled with pulmonary hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension.

NICU nurses play a crucial role in supporting families with babies who have abdominal wall defects by providing comprehensive care and emotional reassurance. We educate parents about the condition, explain treatment plans and the expected course of care, which helps alleviate anxiety. By fostering open communication, nurses encourage families to ask questions and express their concerns, creating a supportive environment. Additionally, we offer practical support, such as guidance on feeding and bonding with their infant. This holistic approach not only enhances the care of the infant but also empowers families during a challenging time. Have you taken care of these babies and their families? I'd love to hear about your experience.

Amanda xoxo

Missed my other newsletters? Click here to read them!

Let's Study Together! Join my Certification Course

References:

Dingeldein, M. (2025). Selected gastrointestinal anomalies in the neonate. Fanaroff and Martin’s Neonatal Perinatal Medicine (12th Ed). Elsevier.

Gallagher, M., Pacetti, A., Lavvorn, H., & Carter, B. (2021). Neonatal Surgery. Merenstein & Gardner’s Handbook of Neonatal Intensive Care (9th Ed). Elsevier.

Wagner JP, Cusick RA. Paint and wait management of giant omphaloceles. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28(2):95-100. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2019.04.005.

Chabra, Anderson & Javid, (2024). Abdominal Wall Defects. Avery's Diseases of the Newborn (11th Ed.) Elsevier

OBimages. (n.d.) Gastroschisis Omphalocele. Retrieved from https://obimages.net/free-gastroschisis-omphlocele/

hey nurses don't miss out

© Copyright 2024. AmandasNICUEd. All rights reserved. | Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy Contact: [email protected]