Welcome to Amanda's NICU Education

Hi! My name is Amanda. I'm a NICU nurse, Clinical Nurse Specialist, NICU Educator... basically your NICU BFF. If you want to talk NICU, I'm here for you! I love everything about NICU nursing and I'm eager to learn and share my knowledge with all my NICU friends.

I have been a NICU nurse since 2009 I am currently a Clinical Nurse Specialist in a Level IV NICU in Los Angeles.

I am passionate about educating the next generation of NICU nurses. I share my knowledge through platforms such as Instagram and Facebook and am excited to have you here on my website!

Click on the button below to sign up for my newsletter filled with NICU education and tips for all experience levels.

Not very many people love taking tests but as a self-acclaimed "forever student" who has taken (and passed) five different certification exams I am no longer afraid of tests! "Way to brag", you might be thinking but I want to help YOU pass your certification exam too!

Introducing Amanda's RNC-NIC Success digital course - your ultimate study companion!

Gain unlimited, on-demand access for life, ensuring you're primed to ace your certification exam.

I'm here to help you succeed and I can't wait for you to share with me that you PASSED the RNC-NIC EXAM!!!

NEC Awareness

May 17 is NEC Awareness Day!

I will never forget one of my long-term primary patients from years ago—a preterm, growth-restricted baby boy. He was progressing steadily in the NICU until, seemingly overnight, everything changed. He was diagnosed with Stage III necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and underwent bowel resection, leading to short bowel syndrome (SBS). He needed a Broviac central line and was dependent on cyclic parenteral nutrition (PN) for growth.

Despite these challenges, he remained the sweetest soul, and his parents were resilient and devoted. They sent me Christmas cards for years after his discharge. Against the odds, he continued to grow and thrive, embodying both the devastation and hope wrapped in an NEC diagnosis.

This experience taught me that behind every NEC statistic is a child and family whose lives are forever altered. The month of May is NEC Awareness Month, and I'm reminded of why our vigilance and advocacy around this disease are so crucial.

⚠️ Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a devastating gastrointestinal disease that primarily affects our most vulnerable patients. The disease involves acute inflammation, bacterial invasion, and necrosis of the intestinal wall.

While most commonly seen in premature infants, particularly those born at less than 32 weeks gestation or with birth weights under 1500 grams, NEC also occurs in term neonates with predisposing conditions such as congenital heart disease or perinatal asphyxia.

NEC is not a singular disease but rather a spectrum of acquired intestinal injuries. This spectrum includes:

Classic NEC: The most common form, typically seen in preterm infants after the initiation of enteral feeds

Cardiac-induced NEC: Related to mesenteric hypoperfusion in infants with congenital heart disease

Atypical or transfusion-associated NEC: Often occurring within 48-72 hours of packed red blood cell transfusion

Term infant NEC: Usually associated with specific risk factors such as hypoxic-ischemic injury or polycythemia

Understanding these subtypes is essential for tailoring prevention strategies and treatment approaches to individual patients.

🌪️The Perfect Storm: Pathophysiology of NEC

NEC's pathophysiology is multifactorial, representing a "perfect storm" of conditions that converge in the vulnerable preterm gut. The key contributing factors include:

1. Prematurity and Intestinal Immaturity

The preterm infant's intestinal tract is characterized by:

Reduced barrier function with increased permeability

Immature tight junctions between enterocytes

Underdeveloped mucosal protective mechanisms

Insufficient production of protective antimicrobial peptides

Immature peristaltic patterns that prolong bacterial exposure

These factors create an environment where the intestinal barrier is easily breached, allowing bacterial translocation and triggering the inflammatory cascade.

2. Microbial Dysbiosis

The preterm infant's gut microbiome differs significantly from that of term infants:

Delayed colonization with beneficial bacteria

Dominance of potentially pathogenic species

Reduced microbial diversity

Higher concentrations of Proteobacteria (including Enterobacteriaceae)

Lower concentrations of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli

This dysbiosis is exacerbated by common NICU interventions such as antibiotic exposure, delayed feeding, and limited exposure to maternal microbiota.

3. Enteral Feeding Considerations

Feeding practices significantly impact NEC risk:

Breast milk reduces the risk of NEC risk 6-10 fold compared to formula feeding

Rapid advancement of feeds may overwhelm the immature gut

Hyperosmolar formulas and medications may damage intestinal mucosa

Human milk is protective through multiple mechanisms:

Immunoglobulins (particularly secretory IgA)

Lactoferrin with antimicrobial properties

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) that promote beneficial bacteria

Growth factors that enhance intestinal maturation

Anti-inflammatory cytokines that modulate immune response

4. Immune Dysregulation

The preterm infant's immune system is characterized by:

Exaggerated pro-inflammatory responses

Ineffective regulation of inflammatory cascades

Overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8)

Increased toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) expression, which recognizes bacterial lipopolysaccharide

Reduced production of anti-inflammatory mediators

This immune dysregulation creates a hyperinflammatory environment that contributes to tissue damage.

5. Impaired Intestinal Perfusion

Circulatory factors that contribute to NEC include:

Hypoxic-ischemic events that compromise intestinal blood flow

Hypotension requiring vasopressor support

Ductal steal phenomenon in infants with patent ductus arteriosus

Reduced microvascular density in the preterm intestine

Impaired autoregulation of mesenteric blood flow

Together, these factors result in a cycle of intestinal injury, inflammation, and progressive tissue damage that characterizes NEC.

(Hackham & Sodhi, 2018)

🚨The Clinical Presentation: Recognizing NEC Early

Early recognition of NEC is critical for timely intervention. The clinical presentation typically includes a constellation of gastrointestinal and systemic signs.

Gastrointestinal Signs

Abdominal distention: Often one of the earliest signs, with progressive worsening

Bloody stools: Ranging from occult blood to grossly bloody diarrhea

Abdominal wall discoloration: Erythema or a bluish discoloration suggesting possible perforation

Palpable bowel loops: Indicating dilated, thickened intestinal segments

Decreased or absent bowel sounds: Suggesting ileus

Systemic Signs

Lethargy, apnea, bradycardia: Reflecting systemic involvement

Temperature instability: Often manifesting as hypothermia

Hypotension and poor perfusion: Indicating septic shock in advanced cases

Metabolic acidosis: Resulting from poor perfusion and anaerobic metabolism

Thrombocytopenia: A common hematologic finding that may precede other signs

Neutropenia or leukocytosis: Reflecting the inflammatory response

Radiologic Findings

Abdominal radiographs remain the cornerstone of NEC diagnosis:

Pneumatosis intestinalis: The radiographic hallmark of NEC, representing gas within the intestinal wall

Portal venous gas: Indicating more severe disease with bacterial translocation

Fixed, dilated intestinal loops: Suggesting areas of affected bowel

Pneumoperitoneum: Representing intestinal perforation, a surgical emergency

Early stages of NEC may show only nonspecific findings such as dilated bowel loops or a gasless abdomen, highlighting the importance of serial examinations and radiographs in suspected cases.

📊Staging Systems: Guiding Management Decisions

The modified Bell's staging criteria remain widely used to classify NEC severity and guide management:

Stage I: Suspected NEC

Mild systemic illness

Nonspecific gastrointestinal signs

Normal or nonspecific radiographic findings

Managed with antibiotics and bowel rest

Stage II: Definite NEC

Moderate systemic illness

Definite gastrointestinal signs

Pneumatosis intestinalis or portal venous gas on imaging

Managed with antibiotics, bowel rest, and supportive care

Stage III: Advanced NEC

Severe systemic illness with cardiovascular and respiratory compromise

Marked gastrointestinal signs with peritonitis

Pneumoperitoneum or other signs of perforation

Requires surgical intervention

Other classification systems incorporate laboratory values, such as thrombocytopenia and neutropenia, which are associated with poorer outcomes and may help identify infants requiring more aggressive intervention.

(Soni et al, 2020)

Arrow 1 shows the branching tree of the portal venous gas. Arrow 2 shows the crescents of pneumatosis. Arrow 3 shows widespread soap bubbling

🍼Prevention: The Best Treatment

Prevention remains the cornerstone of NEC management. Evidence-based strategies include:

Human Milk as Medicine

Mother's own milk (MOM) is optimal, with a dose-dependent reduction in NEC risk

Donor human milk (DHM) is preferable to formula when MOM is unavailable

Human milk-derived fortifiers may offer advantages over bovine-derived products

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) promote a healthy microbiome and enhance gut maturation

Colostrum oral care (aka Oral Immune Therapy) provides local immune benefits even before enteral feeding is initiated

Standardized Feeding Protocols

Evidence-based advancement guidelines reduce practice variation

Slow advancement rates (15-20 mL/kg/day) may be safer for extremely preterm infants

Trophic feeding protocols that maintain gut stimulation shortly after birth

Careful monitoring parameters for signs of feeding intolerance

Standardized responses to feeding intolerance that avoid unnecessary withholding of feeds

Microbiome Protection Strategies

Avoiding unnecessary antibiotics preserves microbial diversity

Limiting duration of empiric antibiotics when cultures remain negative

Early skin-to-skin care promotes healthy microbial colonization

Avoiding H2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors that alter gut pH and microbial composition

Human milk feeding practices that support a healthy microbiome

Antibiotic Stewardship

Discontinuing antibiotics at 36-48-hours when cultures are negative

Narrowing antibiotic coverage based on culture results

Avoiding broad-spectrum antibiotics when narrower options are appropriate

Regular antibiotic timeout discussions among the healthcare team

Tracking antibiotic usage rates to identify opportunities for improvement

Probiotic Supplementation

Meta-analyses support probiotic efficacy in reducing NEC incidence

Multi-strain preparations may be more effective than single strains

Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species are most commonly studied

Safety considerations include risk of translocation sepsis in extremely preterm infants

There is currently no probiotic approved by the FDA to prevent NEC in preterm infants in the United States

Other Promising Approaches

Lactoferrin supplementation shows potential for NEC prevention

Pentoxifylline may modulate inflammatory responses

Stem cell therapies are being investigated for intestinal repair

Amniotic fluid components may promote intestinal development

Toll-like receptor modulators could prevent excessive inflammation

👩🏻⚕️When Prevention Fails: Treatment Approaches

Despite prevention efforts, NEC still occurs. Treatment approaches include:

Medical Management

Bowel rest: Withholding enteral feeds while maintaining nutrition via parenteral routes

Broad-spectrum antibiotics: Typically covering gram-negative, gram-positive, and anaerobic organisms

Gastric decompression: Reducing intestinal distention and bacterial proliferation

Fluid resuscitation and cardiovascular support: Maintaining adequate tissue perfusion

Correction of coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia: Reducing bleeding risk

Serial abdominal examinations and radiographs: Monitoring disease progression

Surgical Intervention

Approximately 30-50% of infants with NEC require surgical management. Indications include:

Pneumoperitoneum: Indicating intestinal perforation

Clinical deterioration despite maximal medical therapy

Abdominal wall erythema or discoloration

Surgical approaches include:

Primary peritoneal drainage: Often used as a temporizing measure in extremely preterm infants

Laparotomy with resection: Removing necrotic bowel segments

Creation of ostomies: Diverting intestinal contents

Long-term Outcomes and Complications

NEC survivors face significant short and long-term challenges:

Gastrointestinal Complications

Short bowel syndrome (SBS): Resulting from extensive intestinal resection

Intestinal strictures: Occurring in up to 35% of medically managed cases

Malabsorption and failure to thrive: Due to reduced absorptive surface area

Recurrent feeding intolerance: Requiring modified feeding approaches

Cholestatic liver disease: Associated with prolonged parenteral nutrition

Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

NEC survivors, particularly those requiring surgery, have higher rates of:

Cerebral palsy

Cognitive impairment

Hearing and visual impairments

Language delays

Behavioral challenges

These neurodevelopmental impacts may be related to inflammatory mediators affecting the developing brain, prolonged hospitalization, nutritional deficits, and associated comorbidities.

Family Impact

The impact of NEC extends beyond the infant to affect the entire family:

Prolonged hospitalization disrupting parent-infant bonding

Financial strain from medical expenses and lost work time

Emotional trauma associated with critical illness

Medically complex children with long-term complications

Increased parental stress and anxiety

Supporting NEC Survivors: The Long Road Ahead

Care for NEC survivors requires a multidisciplinary approach:

Nutritional Support

Specialized feeding approaches for children with short bowel syndrome

Monitoring for micronutrient deficiencies

Growth tracking with adjusted expectations

Transitioning from parenteral to enteral nutrition

Managing oral aversion and feeding difficulties

Developmental Follow-up

Early intervention services

Regular developmental assessments

Specialized therapies (physical, occupational, speech)

Educational support and advocacy

Family support resources

Building Resilience

Despite the challenges, many NEC survivors demonstrate remarkable resilience. Supporting this resilience involves:

Celebrating small victories

Building support networks

Connecting with other NEC families

Focusing on capabilities rather than limitations

Advocating for needed services and resources

NEC Awareness and Advocacy: Making a Difference

May 17th is designated as NEC Awareness Day, providing an opportunity to:

Educate healthcare providers about prevention strategies

Raise public awareness about this devastating disease

Support research initiatives seeking better prevention and treatment

Connect families affected by NEC with resources and support

Advocate for policies that support human milk feeding and optimal NICU care

Organizations like the NEC Society bring together researchers, clinicians, and families to advance prevention, treatment, and support for those affected by NEC.

NEC remains one of the most challenging diseases in neonatal care, but there is reason for hope. Advances in understanding the pathophysiology, improving prevention strategies, and developing targeted therapies offer promise for reducing the burden of this disease.

As NICU nurses, our vigilance in identifying early signs, our advocacy for evidence-based prevention practices, and our compassionate care for affected infants and families make a profound difference. Every baby spared from NEC represents a family saved from trauma and a life preserved from potential long-term complications.

During NEC Awareness Month, let us commit to continued progress toward a future where NEC no longer devastates our most fragile patients.

Resources for Families and Professionals

Let's work together to create a world without NEC.

Wishing you the best

Amanda

References

Keefe G, Jaksic T, Neu J. Necrotizing Enterocolitis and Short Bowel Syndrome. In: Martin RJ, et al. Fanaroff and Martin's Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine. 11th ed. 2020

de la Cruz D, Gipson DR. Moving Beyond NEC. In: Martin RJ, et al. Fanaroff and Martin's. 11th ed. 2020

Ortigoza EB. Feeding Intolerance. In: Kliegman R, et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 21st ed. 2020

National Association of Neonatal Nurses. Neonatal Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: A Resource Guide for the Student and Novice Neonatal Nurse Practitioner. 2020

Neu J, Walker WA. Necrotizing enterocolitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(3):255–264. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1005408

Sharif S, et al. Probiotics to prevent NEC in very preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;10:CD005496. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005496.pub5

Gephart SM, McGrath JM. NEC Zero: A prevention-focused approach. Adv Neonatal Care. 2012;12(1):23–32. doi:10.1097/ANC.0b013e3182425df0

Hackam DJ, Sodhi CP. Toll-like receptor-mediated intestinal inflammatory imbalance in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;6(2):229-238.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.04.001

Hair AB, et al. Beyond necrotizing enterocolitis prevention: Improving outcomes with an exclusive human milk-based diet. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11(2):70-74. doi:10.1089/bfm.2015.0134

Patel RM, Denning PW. Intestinal microbiome and its relationship with necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Res. 2015;78(3):232-238. doi:10.1038/pr.2015.97

How to use abdominal X-rays in preterm infants suspected of developing necrotising enterocolitis. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Education and Practice 2020;105:50-57.

Missed my other newsletters? Click here to read them!

Let's Study Together! Join my Certification Course

December 2023 Certification Review Webinar

NICU Certification Review

Ready to kickstart your journey to becoming a certified NICU nurse?

Look no further!

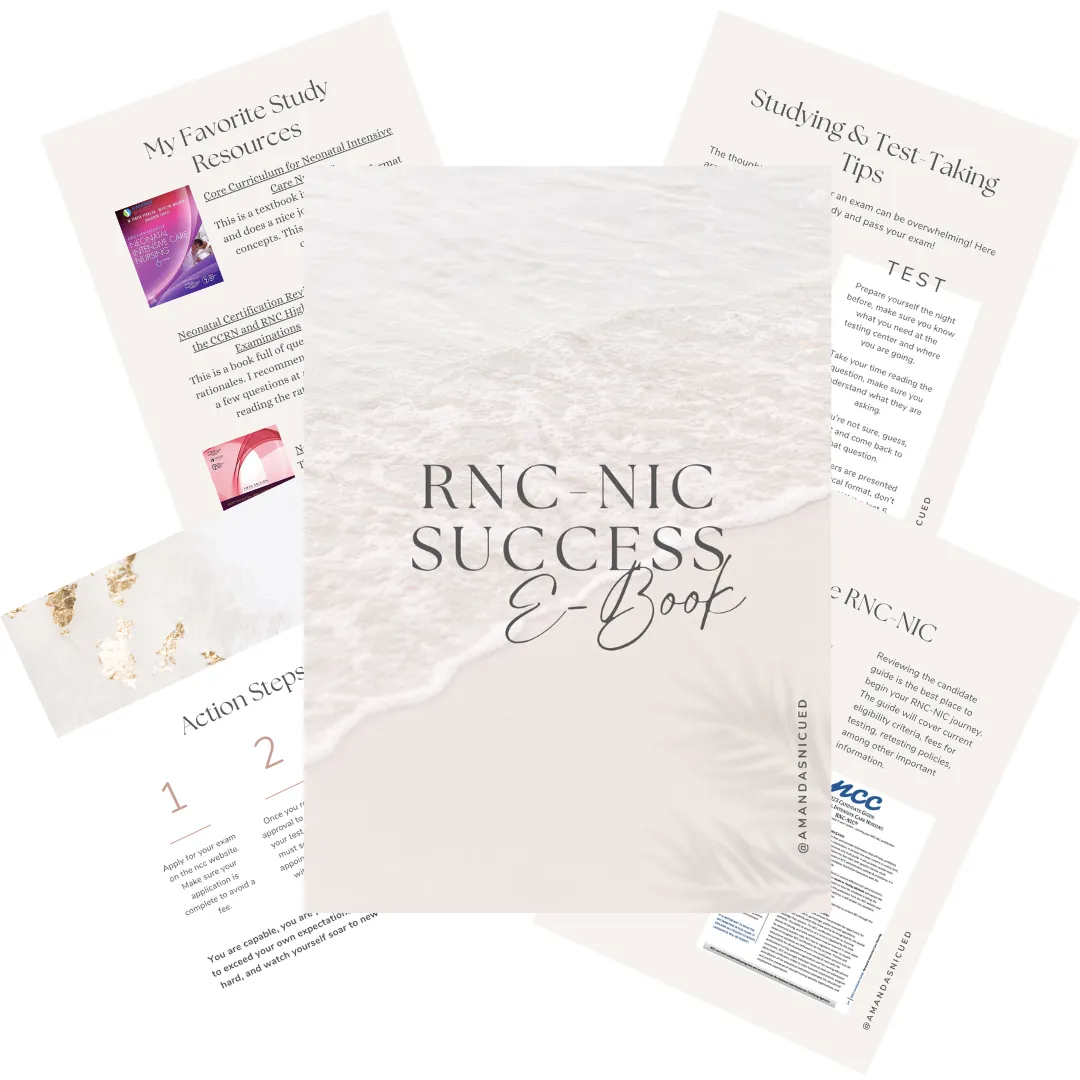

Grab my FREE E-Book packed with essential study and test-taking strategies for the RNC-NIC.

In the E-Book I give you the resources you need including the link to access the candidate guide, several types of books to study from, some of my favorite strategies, an outline of the content you should review, and a blank calendar for you to make your study plan!

Frequently Asked Questions About the RNC-NIC exam

What is the RNC-NIC?

The RNC-NIC is a competency-based exam that tests the specialty knowledge of nurses in the United States & Canada who care for critically ill newborns and their families.

The RNC-NICU is a nationally recognized certification that recognizes the registered nurse for their specialty knowledge and skill.

Who can take the RNC-NIC exam?

Nurses can take this exam after a minimum of two years experience in the NICU caring for critically ill newborns and their families.

Which books should I use?

I'm glad you asked! There are many excellent books to help you prepare for the RNC-NIC, I gathered ande describe each of them for you in my FREE e-book.

Is there a course to help me study?

Yes! Many hospitals host their own certification course and there are a few online courses. See my RNC-NIC test taking tips E Book for more information

What happens if I don't pass the exam?

If you don't pass the exam on your first try you can try again after 90 days. You will have to reapply after 90 days and pay a retest fee. There is no limit to the number of times you can take the exam (however a candidate can only sit for the exam twice per year).

Can I make more money if I take the RNC-NIC exam and get certified?

Yes! Many hospitals provide a raise or a bonus for nurses with specialty certifications. Hospitals also typically hire at a higher base salary when nurses have a certification.

Find me @amandasnicued on these channels or Email me

hey nurses don't miss out

© Copyright 2024. AmandasNICUEd. All rights reserved. | Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy Contact: [email protected]